Bellows-Type Fluoroscope (ca. 1897-1900)

What we have here is a very early and very nice example of a bellows-type fluoroscope. The wooden frame is mahogany and the bellows is leather. The fluorescent screen, a light yellowish-green, is almost certainly barium platinocyanide.

A reasonable guess would be that it dates from 1897 to 1900. Unfortunately, there is nothing on it that would indicate the manufacturer. In fact, there is nothing to suggest that it ever had a label. If there were screw holes that might indicate where a missing plate was attached, they can’t be detected.

One possibility is that this fluoroscope wasn’t sold separately—instead, it might have been a generic device that was supplied to a physician who purchased a complete X-ray system. Since the collection obtained it from a dealer in the UK, it is somewhat more likely to have been manufactured there. Harry W. Cox of London, a well know supplier of X-ray equipment, marketed very similar bellows-type fluoroscopes.

The vast majority of hand-held fluoroscopes had some sort of trim (e.g., fur, silk, cloth) around the viewport in order to create a light-tight seal when the operator was looking at the screen. Our fluoroscope is either missing the trim, or it never had any. The latter possibility shouldn’t be ruled out since the curved wooden flange around the opening provides an excellent seal on its own.

The Bellows

The purpose of employing a bellows rather than a solid body was to allow the operator to adjust the distance between their eyes and the fluorescent screen. Quoting Henshaw (1897):

“The best fluoroscope should be non-phosphorescent, and should be arranged in a bellows frame, with cloth and hood to throw entirely over the head, and then the examiner can adjust the screen at the proper distance from his own eyes to exactly suit his individual eyesight. The result will be a far greater distinctness of details of the object under examination”

Holtz (1911) described the problem associated with solid body (non-adjustable) fluoroscopes thusly:

"Almost all of the fluoroscopes placed on the market have been constructed with frames adapted as nearly as possible to the focus of the average eye. For this reason, many beginners have been unable to distinguish much with the fluoroscope, and have expressed considerable disappointment”

Pusey (1903) recognized the advantage of being able to adjust the screen-to-eye distance, but wasn’t overly impressed:

“this is, of course, a convenience, though in practice not an important one”

One reason for Pusey’s lack of enthusiasm might have been the fact that bellows-type fluoroscopes were bulky and frequently had to be held with two hands.

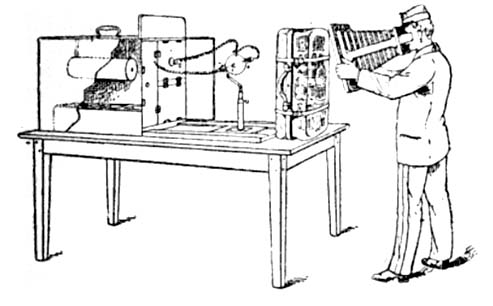

The fluoroscope in the a drawing to the left is very similar to our example (English Mechanic and World of Science, Vol. 66 No 1696 Sept. 24, 1897).

Solid body (non-adjustable) fluoroscopes had a couple of advantages: they were small and they usually came with a downwardly projecting handle that permitted the fluoroscope to be held with one hand. Some bellows-type fluoroscopes had such a handle (see image to right), but they were the exception.

Complaints about the Hand-held Fluoroscope

The following quotes are of E. H. Skinner. He specifically refers to the bellows-type fluoroscope, but he probably would have said the same things about a solid body fluoroscope.

“We must get away from the old type of bellows fluoroscope with which we are familiar, and which the manufacturer supplies you when you buy an x ray outfit. It is absolutely farcical to attempt to draw conclusions from such a fluoroscopic examination” (Skinner, 1911a).

“serves only to promote carelessness and inaccuracy” (Skinner, 1911b).

“The bellows type of fluoroscope is not useful in the least; it leads to incorrect estimates of shadow values and is woefully inexact. It would be splendid if the bellows fluoroscope were eliminated entirely. It is responsible for so many ill-effects and adverse criticisms that we would delight in a bonfire of those now on earth and ostracise the manufacturer of any duplicates” (Skinner, 1911c).

Skinner didn’t provide an explanation for these criticisms, but it was almost certainly related to the fact that the fundamental purpose of a hand-held fluoroscope of the bellows or solid body variety was to permit a fluoroscopic examination without the need to completely darken the room. The problem was that the operator would be unlikely to properly dark adapt their eyes in a partially lit room.

Skinner’s preference was to employ a simple unenclosed fluoroscopic screen in complete darkness. Properly adapting the eyes to these conditions might require at least ten minutes, but to Skinner, the results would be worth it.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t always be possible to perform the examination in a completely darkened room—even after sunset. One reasons for this was that the x-ray tube and the high voltage source (e.g., static machine) could emit light. In this case, the hand-held fluoroscope might prove advantageous.

The Fluorescent Screen

For the image to the right, I opened the door to the compartment that holds the fluorescent screen. This makes it easier for the operator to replace or repair the screen. Or, perhaps, the operator might want to use the screen by itself.

Accessing the screen like this is not always possible with a hand-held fluoroscope.

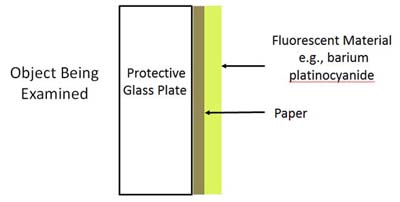

A typical screen consisted of paper, coated on one side with fluorescent material, that was affixed to a lead glass plate. The arrangement is illustrated in the figure below.

General Comments

The screen should be positioned as close as possible to the object being examined in order to improve the sharpness of the fluoroscopic image.

The screen should not be any larger than necessary. Any light coming from regions of the fluorescent screen outside of the area of interest would compromise the operator’s vision. Smaller screens had another advantage: they could sometimes be positioned closer to the part of the body being examined than a larger screen. For this reason, physicians often kept multiple fluoroscopes that varied in size.

After use, the glass should be cleaned. This was particularly important if the glass had been in contact with diseased tissue.

Fluorescent screens were normally stored in the dark.

The performance of fluorescent screens would deteriorate over time and it was believed that low-humidity environments could contribute to this.

In the early days of radiology, before the terminology had been settled, hand-held fluoroscopes were often referred to as cryptoscopes.

Size: Approximately 10" x 12" x 12"

References

- American Roentgen Ray Company. The Roentgen Rays, Their Production and Use. 1897.

- Henshaw, G.B. The X-ray with the New Holtz Machine; Some of its Applications in Medicine and Surgery. Ann. Med. Practice. Vol. 10. 1897.

- Pusey, W.A. The Practical Application of the Roentgen Rays in Medicine. 1903.

- Skinner E. H. Medical Herald Vol. 30. July 1911a.

- Skinner, E.H. The X-ray Chimera. Medical Brief. Vol. 39. July. 1911b.

- Skinner, E.H. Fluoroscopy of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Am. J. Med. Sci. Vol. 141. 1911c.