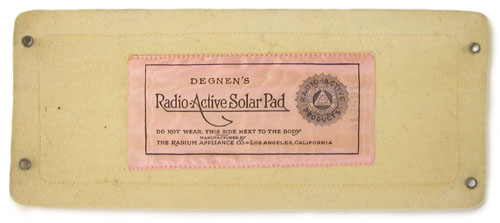

Degnen's Standard Radio-Active Solar Pad (1915-1930)

M.L. Degnen, "the man who made this pad possible," has been associated with the development of the science of "radio-activity" since its inception. The knowledge thus gained has culminated in the "Radio-active Solar Pad," or so stated the literature of the Radium Appliance Company of Los Angeles.

Donated by Phil Nieberg.

This device was somewhat unusual in that it was supposed to be charged in sunlight prior to use. The manufacturer explained that its "radio-activity is further increased by exposing the pad to sunlight" and "when applied to the body, the pad immediately begins to discharge this energy into the system, sending the lifegiving current through the blood and nervous system."

The first version of the pad (ca. 1918-1925), such as that shown above, contained purified radium. Pads produced after 1925, like that in the lower photograph, employed uranium ore as the source of radiation. The company's advertisements from 1926 (e.g., Anaconda Standard, April 4, 1926) and possibly those of the previous year, explained that they began using Carnotite ore as a way to keep the pads affordable. They trumpeted the scientific breakthrough that made this possible as follows: “The laboratory of the Radium Appliance Company has succeeded in working out a scientific process whereby Carnotite ore of the highest grade in Radium content is stimulated and fortified by the addition of actual Radium purchased through the Bureau of Standards, Washington.” Of course, cynics might claim that the company’s real goal was to increase profits—uranium ore was far less expensive that purified radium.

Donated by Rutgers University courtesy of Patrick McDermott.

Size: ca. 4" x 10"

Exposure rates:

- Approximately 35-40 uR/hr above background at one foot for the radium containing pad (top photo)

- Approximately 1-2 uR/hr above background at one foot for the uranium containing pad (bottom photo)

In the early days, Degnen’s Radio-Active Solar Pad was priced at $15. By 1924, the price seems to have been increased to $17.50. At some point the company began selling multiple models of the pad. A Radium Appliance Company letter dated 1927 indicated that in addition to the standard pad there was a “Physicians Special $50 model” and a $100 “strong Physicians Special Pad. The different choices gave someone who didn’t obtain results using a less expensive pad the option to spend more money. The following is taken from a Radium Appliance Company letter to a customer whose wife was making slow progress: “your wife is using our mildest Pad and if I were you Mr. Blake I’d have her change to this strong Physicians Special Pad—the $100 model.” “I know that if she were a member of my family that I would insist on this.” Another letter reminded the same man “What does money amount to... nothing in the world.

Degnen’s Radio-Active Solar Pad was definitely popular. By 1930, advertisements proclaimed that over 150,000 had been sold (e.g., Cedar Rapids Sunday Gazette and Republican, August 24, 1930). A sales figure like that is not surprising if, as the company claimed, “Degnen’s Radio-Active Solar Pad will benefit about 95% of all human ills.”

Even Edgar Cayce, the internationally acclaimed psychic, recommended the pad. In fact, Cayce exchanged letters with John Dutcher of the Radium Appliance Company regarding the best use of the pad.

The accompanying drawing (from a company advertisement) shows M.L. Degnen inspecting one of his pads. Next to the pad is a Lind electroscope, just like that in the ORAU collection!

Read about Degnen's Eye Applicator, another radium-containing product from the Radium Appliance Company.

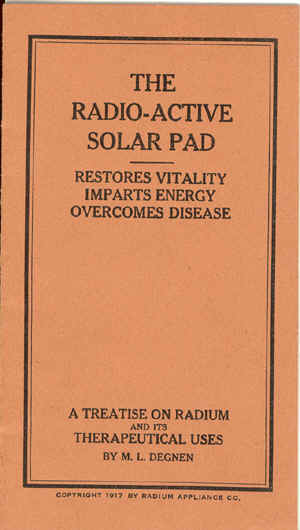

Even though an advertisement in the May 27, 1930 issue of the Amarillo Globe indicated that the Radium Appliance Company was established in 1916, the earliest contemporary references I have seen to the company were from 1917, e.g., a booklet written by M.L. Degnen regarding his Radioactive Solar Pad, and a newspaper advertisement that appeared September 14, 1917.

Degnen’s personal listing in the 1917 edition of the Los Angeles City Directory indicated that he was associated with the Solar Energy Company. It wasn’t until 1918 that the Radium Appliance Company was mentioned in the Directory.

Since the City Directory data might have been collected the year before it was published, it is reasonable to speculate that Degnen started the Solar Energy Company in 1916, and that the latter morphed into the Radium Appliance Company sometime in 1917.

In 1917, the following three “members” of the Radium Appliance Company were identified in a notice concerning the company’s incorporation (Southwest Builder and Contractor. Volume 5, August 31, 1917): M.L. Degnen, E.L. Campbell and B.A. Hatch. The same individuals were linked to the company in the 1918 Los Angeles City Directory. These were the last references I have found to Campbell and Hatch in company-related literature.

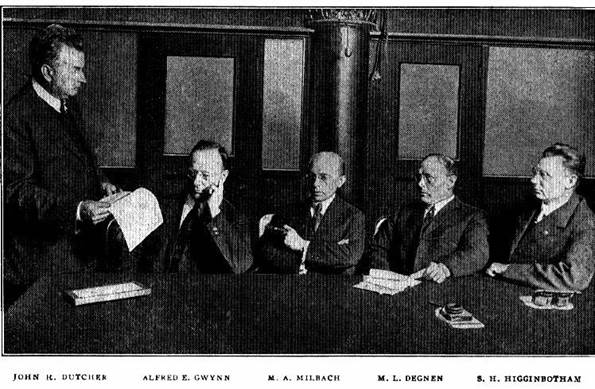

By 1919, and through most of the 1920s, Radium Appliance Company had five key players: M.L. Degnen, J.R. Dutcher, A M. Milbach, A.S. Gywnn, and S.H. Higginbotham (see the following image from a company flyer 1921).

They modestly described themselves as follows: “we are just ordinary business men here in Los Angeles whose word and credit is good at any bank—the same kind of men as you have in your own community”

Michael Lawrence Degnen. Degnen was the man who founded the company and served as its president from its beginnings (1916/1917) until its demise (ca. 1933). He usually identified himself as a chemist in his personal listings in the Los Angeles City Directories.

John R. Dutcher. Dutcher seems to have functioned as the company’s sales manager and oversaw their extensive advertising campaign. When you were looking to purchase their products, seeking information or registering a complaint, you interacted with him.

Marinus A. Milbach. According to Radium Appliance Company literature, Milbach was “formerly part owner and foreign buyer for one of the largest department stores in Los Angeles.” For most of its history, 1925 through 1932, Milbach was identified as the company’s secretary. The last document I have seen identifying the company’s directors, the 1932 Los Angeles City Directory, lists Milbach, Dutcher and, of course, Degnen.

Samuel H. Higginbotham. Higginbotham was described as previously being a “part owner and representative of one of the largest rubber companies in America.” Although it seems that he focused on sales, he also patented one of the company’s most impressive radioactive products: the Sta-Put Truss (“it supports while it heals”). Higginbotham’s background in sales probably gave him a good idea of what his customers needed. Sometime in 1925 or early 1926, he left Radium Appliance Company to become vice-president of Angelus Manufacturing Company.

Alfred E. Gwynn. A pamphlet produced by Radium Appliance Company said that Gwynn had been “President of the Board of Directors of one of our largest hospitals” and that he “probably built more houses in Los Angeles” “than any other one man.” The Los Angeles City Directories from 1920 to 1925 identified Gwynn as a company manager. His job title changed to vice-president in the 1926 City Directory. In the City Directory for 1927, he was still listed as a vice-president, but not of Radium Appliance Company - he was now working for the Associated Mortgage Company of L.A.

Although Higginbotham and Gwynn seem to have left Radium Appliance Company at about the same time, ca. 1925-1927, the company continued to use a letterhead with their names on it as late as 1930. In any event, it is interesting to speculate that their departures might have been related to M.L. Degnen’s legal troubles.

Michael L. Degnen was unlucky in love. The same could be said for his wives.

His first marriage only lasted ten years, his wife Grace passed away in November, 1921 at age 39. He was 51.

A year and a half after Grace’s death, Degnen’s began a relationship with Eloise Clement. Yes that Eloise Clement, star of the screen and stage. If her name doesn’t ring a bell, you might recall her role alongside Marion Davies in the 1918 film “Burden of Proof.”

Michael and Eloise were years apart in age, and their time together was brief, but they burned both ends of the candle. A case in point was their day trip to Tijuana Mexico where they spent most of a day in the Mint Saloon getting “heavily intoxicated” - Degnen would recall his bad hangover on the trip back to LA. Rather than going straight home, they decided to stop in La Jolla and spend three days in the Cabrillo hotel registered as “husband and wife.” Oddly enough, as Eloise remembered it, they went to San Diego in order to perform certain tests with experimental photographic equipment. She didn’t recall Tijuana. And the only reason they stopped at the hotel in La Jolla was that Michael became ill.

Despite being a professional actress, Eloise shared Michael’s interest in science. She recalled visiting Degnen’s laboratory in the Bradbury Building, almost always at night, where they would “conduct experiments.” These visits occurred as often as three or four evenings a week.

Unfortunately, the nature of these experiments became a point of contention between the defense and prosecution when Eloise testified against Michael in court. The following exchanges between the Defense lawyer and Eloise were typical::

Question: “you say you went to the laboratory to perform some work. State what was done, any work that took you three hours to do.”

Question: “Isn't it a fact that you went there and stayed with Mr. Degnen until about a quarter after 1 o'clock, and that there was no experiment of any kind conducted by you or him at that time?"

Answer: “Mr. Degnen acted in the position of my preceptor; he was teaching me.”

Question: “Then I would like to know what he taught you that night.”

This last comment outraged the prosecuting attorney:

“I object to that as incompetent, irrelevant and immaterial.”

Another witness, the night foreman in the Bradbury Building, testified to the late hours that Michael Degnen and Eloise Clement devoted to science. He recalled one occasion when the two of them left the building at 3 o'clock in the morning.

Testimony from a building janitor indicated the significant level of effort they would expend in their desire to conduct their experiments. He described their arrival at the building one night after the elevator had ceased running, something that usually happened at 9 o'clock. “They were both so intoxicated that they had to help each other upstairs, both falling in doing so, and that it took about ten minutes for them to get to appellant's rooms, which were on the third floor.”

Their “romance” ended the evening of July 30, 1923 with a nasty brawl that left both of them with multiple injuries. According to the case report: “The undisputed evidence is that on the next day they both showed on their persons ample evidence of the fact that they had been in a "fight" and that “Beyond dispute, E.C. was severely injured during the physical encounter.” Among other things, Eloise had suffered a fractured clavicle.

Eloise did more than call off the relationship however. She also filed felony charges with the police with the result that Michael L. Degnen went to trial under a two-count indictment.

- The first count: assault with intent to murder.

- The second count: rape.

In his defense, Degnen blamed the altercation on their intoxicated state and the stress induced by her financial demands—he testified that she called him a piker” and complained that he “was not coming through.”

But the jury was unsympathetic. On December 16, 1923, Michael L. Degnen was convicted on both counts. He was sentenced to no more than 25 years in prison and fined $500.

Eloise was elated and announced in the press that she intended to give up acting, become a lawyer, and specialize in prosecuting mashers. She might have celebrated too soon.

Degnen immediately appealed the court’s decision, and on January 30, 1925 his conviction was overturned.

The president of Radium Appliance Company had dodged the proverbial bullet, and was now in a position to fully devote himself to company affairs. But there were forces beyond his control, and those of every other manufacturer of radioactive consumer products: the deaths of the radium dial painters, the great depression, and the clampdowns by the Department of Agriculture and the Federal Trade Commission. By 1934, Radium Appliance Company had ceased to exist, or was in its final days.

With not much happening at the office (or laboratory), Michael L. Degnen was ready for another shot at love. In January of 1934, Michael had a new bride. Antoinette was 47. He was 63.

Unfortunately, this marriage was even shorter than the first. Antoinette died in 1938, within four years of becoming Mrs. Degnen.

Both of his wives died at a relatively young age, Grace at 39 and Antoinette at 51. Michael L. Degnen passed away in January of 1945, at age 74.

References

- Bluefield Daily Telegraph. Wednesday, January 30, 1924, Bluefield, West Virginia.

- Degnen, M.L. The Radio-Active Solar Pad. A Treatise on Radium and its Therapeutic Uses. Marvels of Radium (and Its Value as a Curative Agent). Radium Appliance Company. 1917.

- People v Degnen, 70 Cal. App. 567 (Cal. Ct. App. 1925).