ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity includes radium water jars

On the Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity’s website, it’s filed under “radioactive quack cures,” and in our physical museum, you can find this topic in a section we call “off the market.” I’m talking about water jars—water jars that boasted using radioactive materials for health benefits. We wrote about this in our blog about radium water jars from the 1920-30s, and now I want to back up and explain where the idea of consuming water infused with radium originated.

The discovery of radioactivity at the end of the 19th century sparked widespread fascination and curiosity, influencing various fields of science, medicine, and even the cultural perception of health. When scientists identified the presence of naturally occurring radioactive elements, such as radium, in certain mineral springs, these waters were quickly linked to potential therapeutic benefits. This connection emerged during a time when the curative properties of hot springs and mineral waters were already well-recognized, and the newfound understanding of radioactivity added a novel layer to their appeal. Many consumers claimed that soaking in and/or drinking the water could boost energy and improve overall well-being.

Picture from Hot Springs, Arkansas. Credit: Getty Images, Richard Wood

The association between radioactivity and health benefits was largely driven by the belief that exposure to small amounts of radiation could stimulate biological processes and promote healing. (Read more about how ORAU’s Medical Division used radioisotopes in cancer therapy!) Springs containing trace amounts of radon gas or radioactive minerals were thought to enhance circulation, relieve pain, and rejuvenate the body. Physicians and entrepreneurs capitalized on this perception, marketing "radium baths" and other treatments as cutting-edge remedies for ailments ranging from arthritis to fatigue. Resorts and spas built around radioactive springs flourished, offering visitors the promise of health and vitality through immersion in these "miracle waters."

Have you heard of Hot Springs, Arkansas? It’s home to 47 thermal springs, and those springs put the city on the map, so to speak. The U.S. Congress designated Hot Springs as a federal reserve in 1832 and later established the area as Hot Springs National Park in 1921. Tourists have been flocking there ever since.

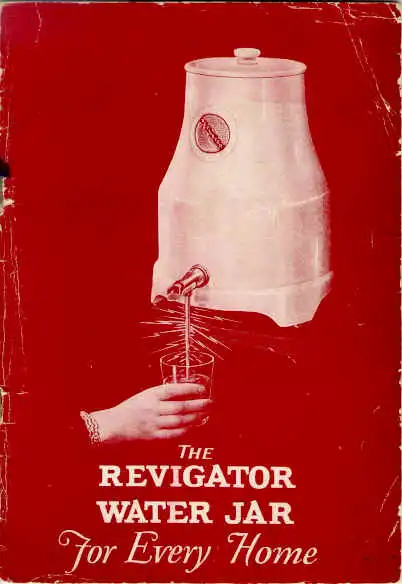

Brochure for The Revigator Water Jar from 1927-1930.

Paul Frame, Ph.D., is a retired ORAU health physicist and trainer. He’s also the curator of ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity. He explained the logic of the time when he originally wrote an article about radium water jars in the Nov. 5, 1989, edition of the Oak Ridger: “There was a downside to the euphoria [as it relates to the health benefits of radium in water]: radon cannot remain in the water very long before it decays or escapes into the air. Because of this, water bottled at the spring does not survive. Its ‘life element’ is lost before it can be consumed. Radioactive water must be drunk at the spring to be effective. How then could the poor and infirm benefit if the costs and effort of traveling to the springs were prohibitive? The solution came with the invention of devices that could be used in the home to add radon to drinking water.”

What resulted was a host of products that claimed to offer consumers the same benefits of visiting these health springs—but in the convenience of filling your own water glass at home. So, that’s why water jars (and several of them in fact) are in our museum collection. Because of the material the jars are made from or the inserts within them, they still read too hot to be on display. We keep them in our vault. (Look at how many we have! Since they’re locked away, I scrolled through them on the museum website in this quick video clip.)

While there’s credibility in the use of radioactive materials in medical applications, the understanding of radiation’s risks was limited in the early 1900s, and the long-term dangers of exposure were not yet fully appreciated. As a result, the use of radioactive springs and related products persisted for decades before the health hazards of radiation became more widely understood.