William Pollard, Ph.D., looking at a portrait of himself in the Pollard Auditorium on ORAU’s campus in Oak Ridge, Tenn.; photo credit: Ruth Carey, Oak Ridge Public Library Digital Collections

Throughout history, few individuals have held the diverse titles of nuclear physicist, author, teacher, administrator and Episcopal priest all at once. Yet, William Grosvenor Pollard (1911-1989) uniquely embodied this remarkable combination. Over the course of his 40-year career, these seemingly divergent roles often intersected, showcasing his multifaceted brilliance. Those who knew him fondly recall his ever-present smile and signature pipe.

This is the story of Dr. William G. Pollard, the visionary founder of Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU).

William Pollard’s background

Pollard was born in Batavia, New York, which is about an hour’s drive from Niagara Falls. When he was 12, his family moved to Knoxville, Tennessee, and the Volunteer State would become his lifelong home. Pollard attended the University of Tennessee and received his bachelor’s in mathematics in 1932. That same year, he married Marcella, a woman who profoundly influenced his life. Together, they raised four sons. Pollard went on to earn his Ph.D. in physics from Rice University in 1934.

Marcella, who grew up in Nashville, Tennessee, was deeply rooted in her Christian faith. She expected her husband to attend church with her, but Pollard, despite his own Christian upbringing, had embraced skepticism and described himself as anti-religious. In an interview with The New Yorker, Pollard reflected on a pivotal moment early in their marriage:

“Three months after our wedding, I remember, Marcella very much wanted me to go to church with her one Sunday, but I told her that the studying I was planning to do at home was more important. The church was a mile away, and she told me later that as she walked toward it alone, she kept looking back, hoping that I would be trying to catch up with her. I was doing no such thing, but neither could I get any work done as I sat at home thinking of her. And since I couldn’t, I figured that one of us might as well have our way, so after that I went to church with her. But I wouldn’t say the creed. I considered it too ridiculous.”

Dr. William Pollard founded ORAU and served as its executive director for 28 years.

While Pollard may have been skeptical of religion at the time, he was unwavering in his passion for science. He felt incredibly fortunate to be studying physics during what he considered a golden age of discovery. The year before he began his graduate studies, James Chadwick discovered the neutron, opening the door to other groundbreaking advancements. Pollard’s education was peppered with revelations from luminaries such as Marie Curie who shaped the field of physics. In 1935, his Ph.D. thesis focused on a theory Enrico Fermi was advancing about beta radioactivity. Fermi went on to win the Nobel Prize in physics in 1938. For Pollard, it was an exhilarating time to be immersed in the world of science, surrounded by innovation and discovery.

After earning his doctorate, Pollard moved his family back to Knoxville and joined the University of Tennessee faculty as an assistant professor of physics. In a 1980 article entitled “The Coming of Age of Southern Universities in Science” Pollard described returning to UT in 1936 “full of ambitions and dreams of continuing this heady course of development. The eight years that followed were quite productive for me personally, but the isolation of the university from the centers of action was depressing. Southern universities were almost exclusively devoted to teaching while schools in the north and west had all the excitement of research and discovery.”

This realization set the stage for a serendipitous task that would change the trajectory of his career—and Southern universities—forever.

Setting the stage: How ORAU came to be

Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) traces its origins back to October 1946, when it was established as the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies (ORINS). It was a year after World War II ended, and its founding represents a pivotal moment in American history, born from the foresight of two visionary physics professors—Katharine Way, Ph. D., and William Pollard—whose conversation at a dinner party laid the groundwork for the organization’s creation.

A few years earlier, in 1944, the world was engulfed in conflict, with the United States committed to ending the threat to democracy at the hands of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. President Roosevelt had secretly authorized the clandestine Manhattan Project, and thousands of men and women (military and private citizens) were working feverishly to complete the first nuclear weapon, whether they knew it or not.

Katharine “Kay” Way. Image courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Wheeler Collection, via ORNL Review.

In this effort, top researchers in various fields were recruited to drop what they were doing and help get this work to the finish line. That call included Way and Pollard, who both taught at UT. Way went to work for the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago and joined the efforts to develop nuclear chain reaction calculations and reactor design. Pollard reported to Columbia University in New York and conducted research on the gaseous diffusion method of extracting uranium 235 (the explosive in atomic bombs) from common uranium.

When the mission was complete and the bomb ended the war, life resumed its familiar rhythms. Pollard found himself back at his teaching position at UT. Way moved back to the area but worked in Oak Ridge rather than at the university. It was at a dinner party in October 1945, that she and Pollard had the opportunity to catch up and discuss the future of the federal facilities built during the war. Both professors lamented the perception of Southern universities as second-rate compared to prestigious institutions in the Northeast and on the West Coast.

William Pollard, Ph.D., is pictured center right holding his pipe at the first ORINS council meeting on Oct. 17, 1946.

Way talked about what was happening with the universities around Chicago and how there were plans to continue nuclear research. She suggested something similar should be done with the complex in Oak Ridge because that would ensure the region would maintain an open door to scientists and critical research opportunities for UT and elevate the reputation of Southern universities. This was just what Pollard was waiting to hear. He loved the idea and saw it through, as Way decided to move on to other projects, particularly focusing on nuclear data.

In the following months, the head of UT’s Physics Department agreed to give Dr. Pollard time to spearhead the formation of a consortium of 14 universities. This group would advise the federal government on training and hiring scientific personnel and facilitating collaboration between researchers and educational institutions. On Oct. 14, 1946, (about a year after Dr. Way and Dr. Pollard had that dinner party conversation), the state of Tennessee granted Pollard the charter of incorporation for ORINS, marking the official beginning of what we now know as ORAU. The first council meeting met days later.

The front page of the Oak Ridge Journal documented the first ORINS council meeting.

The organization’s impact was immediate and deep. According to the ORNL Review, Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s research magazine, “The existence of ORINS played a pivotal role in the decision to keep Oak Ridge’s Manhattan Project facilities funded,” as noted by Lee Riedinger, retired University of Tennessee physics professor and former deputy for science and technology at ORNL.

Pollard shared the same sentiment. In his article “The Coming of Age of Southern Universities in Science.” He wrote, “The accident of the war which placed ORNL in the wilds of East Tennessee can be seen in retrospect to have been a major factor in this transformation. ORAU, because of its early formation soon after the war, was able to secure a large participation of the southern universities in ORNL and so to maximize its impact on higher education in the region. As one whose professional career spans both the pre- and post- war periods covering a full half century of this history of southern universities and who was in a position to seize the opportunities as they arose, I take great personal satisfaction from the role that I was privileged to play in this achievement.”

Early initiatives and expansion

In its early years, ORINS prioritized graduate training programs, research participation opportunities, and isotope tracer techniques. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)—now the Department of Energy—soon expanded ORINS’ scope to include nuclear medicine research. This led to the establishment of the ORINS Medical Division, one of three designated cancer research hospitals in the country at the time. Under the leadership of pioneers like Marshall Brucer, Gould Andrews, Karl Hubner and Nazareth Gengozian, the Medical Division achieved significant advancements in nuclear medicine.

Dr. Pollard (second from left) shows the ORINS Medical Division cobalt machine to visitors; photo credit: Ruth Carey, Oak Ridge Public Library Digital Collections

You can practically hear Pollard brimming with pride as he put on his executive director hat and wrote the “ten-year appraisal” in ORINS’ 1956 annual report: “Probably no one can observe the first blundering steps of a small child without occasionally marveling that he eventually grows up to be an adult capable of carrying out the most complicated mechanical and mental procedures smoothly and efficiently,” the 10th Annual Report started out. “By the same token, a survey of the beginnings of the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies can only make one marvel that it has grown, in the space of 10 years, to be the organization that it is today.”

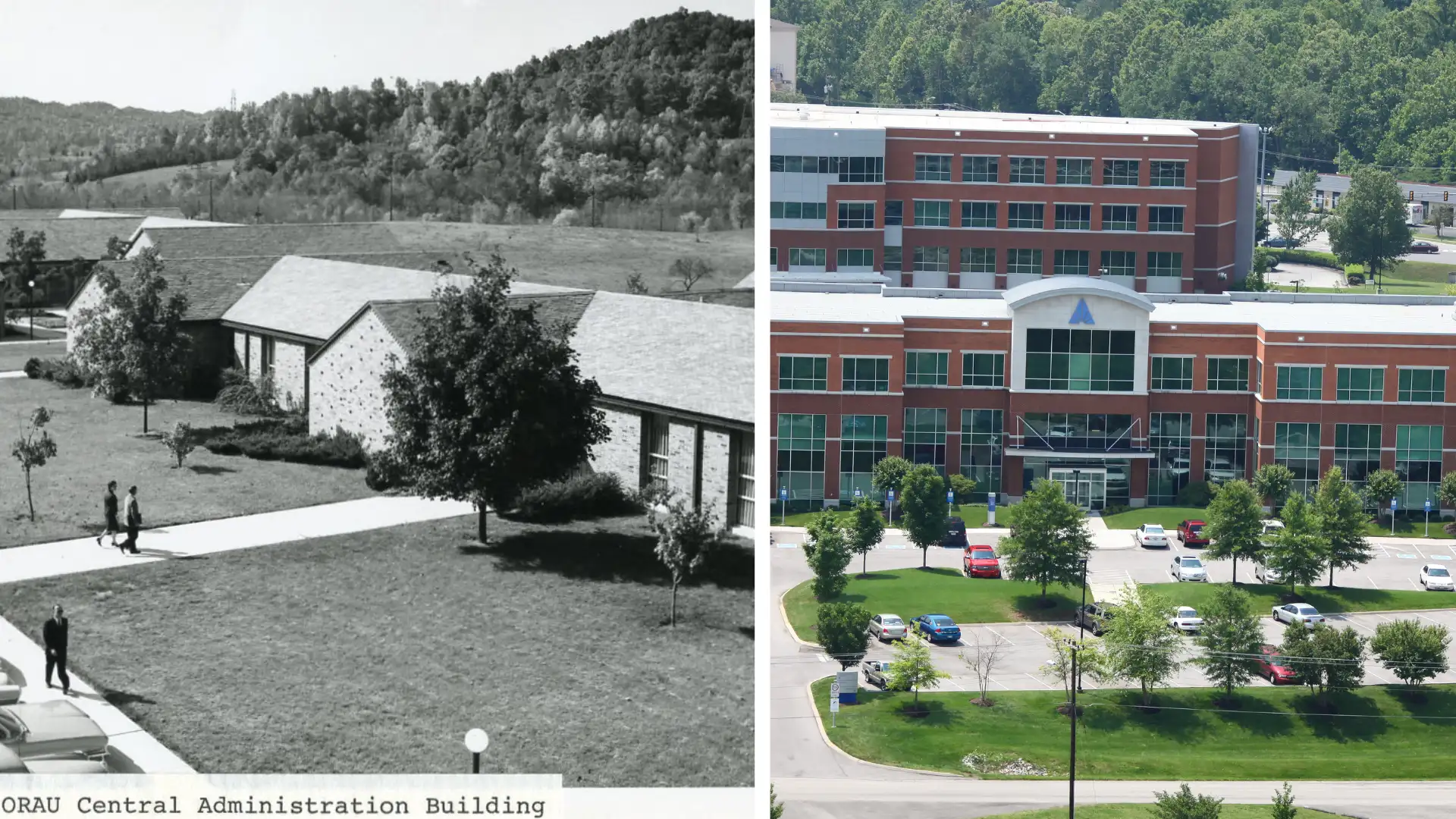

ORAU integrates academia, government and industry to advance the nation’s learning, health and scientific knowledge. Pictured is ORAU in its early beginnings (left) and ORAU’s main campus today.

The growth continued, and a decade later, the 1965 annual report recorded that ORINS’ meeting of presidents and council representatives voted to change the name of the organization to ORAU, or Oak Ridge Associated Universities.

Now 79 years later, our university consortium members are more than 160 strong and our corporate capabilities range from research and STEM education to workforce solutions, public health to environmental solutions, health physics training to peer review, and beyond.

From skeptic to priest

William Pollard stands in front of the ORINS Medical Division.

While Pollard’s contributions to science were monumental, his journey into faith was equally transformative. After his initial reluctance, Pollard regularly attended the Episcopal church with his wife and sons, but he didn’t consider himself particularly religious—that is, until he watched what unfolded in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Dr. Pollard was pleased when he realized his work contributed to the success of the Manhattan Project, but when a second bomb was dropped, those emotions shifted. “After the Nagasaki bomb, my exuberance was replaced by something approaching terror,” Pollard told The New Yorker. “I thought the bombs would be sprinkled all over Japan.”

This moral reckoning led Pollard to embrace his faith more deeply. He became more actively involved in the development of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Oak Ridge whenever he wasn’t at work. In his interview with The New Yorker, Pollard remembered this time of his life when he was open to helping his baby church grow. “At best I might have wound up a good, solid Episcopalian, but Oak Ridge was only five years old, and its churches had little or no resources. It was hard not to lend a hand, but if you did, you let yourself in for more than you bargained for.”

William Pollard was ordained as an Episcopal priest after two and a half years of intense theological study.

It began with a simple question. When Pollard asked the rector whether their parish, which had been meeting in a school gymnasium, would ever have a building of its own, he was met with a request to lead the fundraising effort. Pollard quipped that, having raised the issue, he felt obligated to accept the challenge. His dedication paid off, resulting in $8,000 for the building fund. (The equivalent in 2025, is more than $107,000!)

Soon after, the rector approached Pollard again. This time, he asked him to help with Sunday school lessons. “I wanted to turn him down,” Pollard said, “but I had four children going to Sunday school—more than most of the parishioners—so I was stuck.” True to his nature as a lifelong learner, Pollard began digging into scripture so he could better understand and explain the message of Christ. That got his own intellectual wheels turning in a challenging and satisfactory way that he didn’t expect. “I had to read up on the subjects at the library. I was amazed at how absorbing the material was,” he told The New Yorker.

From there, Pollard became a licensed lay reader, which lead to hours of study. “Here was a field of bona fide scholarship that commanded my intellectual respect, without which, I imagine, I couldn’t have embraced religion. It was exciting to find that the Bible didn’t have to be accepted solely on the basis of its philosophical and metaphysical values. It could be accepted as a piece of history describing the unique fortunes and experiences of a people, which culminated in the revelation of God among them,” Pollard explained.

When he realized he had already spent so much time reading seminary materials, he decided to take the step toward the diaconate—an order of the ministry just below the priesthood that carries with it the privilege of assisting with communion and possibly delivering sermons. “The idea of having my religious studies organized, as my scientific studies had been appealed to me,” he said. “I could always quit at any time along the way. I’d say that my approach then was more curious than dedicated.”

St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, Oak Ridge, Google Maps (street view) today.

Thanks to his scientific notoriety, Time Magazine even dubbed Dr. Pollard the “atomic deacon” in an article they published in 1951. During this time of formal study, his wife later reflected, “Bill’s only recreation was doing carpentry and rolling asphalt walks for the church we were building,” Mrs. Pollard told The New Yorker. The church building was completed in the middle of 1951.

In 1952, at 41 years old, he was invested as a deacon with holy orders in ceremonies held at St. Stephen’s Church—a church he literally helped build with his own hands. His four sons served as acolytes.

One more round of intense study and examination, and William Pollard, Ph.D., was ordained as an Episcopal priest in 1954. Mrs. Pollard told The New Yorker, “And all I ever hoped was that maybe Bill would go to church on Sundays.”

Faith and science

While building ORAU and St. Stephen’s ministry simultaneously, Pollard was preoccupied with theology. He had come to believe that science was a way to investigate the wonders of God’s creation. Articles he wrote such as “God and the Atom” are still discoverable in online archives of the Episcopal Church today.

William Pollard is pictured at a computer with his pipe.

Pollard’s voice was uniquely important in post-World War II science-religion dialogue. The man who graduated from Rice University with a Ph.D. in physics is the same man who bi-vocationally served his church in the clergy. As a man whose career and calling straddled both worlds, he took opportunities to deliver lectures and write books addressing the struggle between advancing nuclear science and its potential consequences. Listen to a convocation address he gave to Augsburg University on April 18, 1963, in which he spoke of “Dark Ages in the Twentieth Century.”

The Oak Ridger, a local paper, took notice of and published one of Pollard’s sermons addressing nuclear warfare. In this message, he told his congregation, “The genie has been let out of the bottle and there is no way to put him back.” He went on to acknowledge man’s fallen nature and how that relates to God.

Dr. Pollard follows behind Billy Graham (pictured walking front left) who was in Oak Ridge to speak to scientists May 23, 1970; photo credit: Ruth Carey, Oak Ridge Public Library Digital Collections

“Perhaps if men were not men but angels, disarmament would be feasible. But men are self-centered and prideful sinners, and a world without a single nuclear weapon in it would be a fearfully dangerous world… All mankind cries out for a Savior who will save him from his most stubborn intractable enemy, himself.”

He even met with evangelist Billy Graham who hosted a crusade stop in nearby Knoxville. Graham made time to speak with a group of a few hundred scientists in Oak Ridge about integrating faith and science, and Pollard was one of the men to welcome him to town.

William Pollard’s legacy

In 1974, upon reaching the age of retirement, Dr. William G. Pollard stepped down from his role as ORAU’s executive director. However, his commitment to science and the organization’s mission persisted. He continued working for several years as a distinguished scientist in ORAU’s Institute for Energy Analysis, contributing his expertise to energy-related research.

Dr. Pollard was a nuclear physicist, author, teacher, administrator and Episcopal priest.

Recognizing the vital role ORAU had played in the story of Oak Ridge as well as its profound impact on East Tennessee and Southern universities, Pollard resolved to document the organization’s history. He authored “ORAU: From the Beginning,” a book that chronicles the origins and evolution of ORAU.

Pollard’s determination to complete this book was steadfast, even as he endured intervals of physically devasting experimental therapy. In 1972, he had been diagnosed with malignant melanoma on his forehead—a battle he faced with both faith and cutting-edge treatments. Despite the challenges of his illness, he continued his work, demonstrating remarkable resilience.

Throughout his health struggles, Pollard also remained dedicated to his spiritual calling, serving as a priest associate at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church up until his death. His commitment to both science and faith defined his later years. On Dec. 26, 1989, Dr. Pollard succumbed to cancer. Though absent from the body, he left behind a legacy of perseverance, brilliance and service to his community.

Looking ahead

Nearly eight decades after its founding, ORAU remains a leader in advancing science, education and workforce development. From its humble beginnings as a consortium of 14 universities, ORAU has grown into a robust organization with diverse capabilities, driving progress in areas of national priority.

As the world experiences a nuclear renaissance, ORAU is providing leadership in preparing the nuclear energy workforce. With our roots reaching back to World War II, we’re priming today’s labor pool for the Manhattan Project 2.0, which will require new skills, more training and enhanced educational experiences to answer challenges of the modern-day nuclear energy industry. We know Dr. Pollard would be thrilled. In an article The Oak Ridger published entitled “William G. Pollard: Man of Science, Man of God” Pollard said this, “nuclear energy is the universal common and natural kind of energy in creation as a whole.” He said he saw the emergence of nuclear power as a clear example of God’s providence.

Picture from ORAU’s main campus in Oak Ridge, Tenn.

Pollard led our organization through the first nuclear era as the Oak Ridge Institute for Nuclear Studies, and he’d be proud of how we’re trailblazing now with our Partnership for Nuclear Energy initiative and ORAU’s Nuclear Energy Academic Roadmap, among others. His legacy of innovation continues to inspire ORAU as we forge new paths in advancing nuclear energy and academic collaboration for the challenges of tomorrow.

To learn more about our journey, watch this five-minute video that answers the question: What is ORAU?

Sources:

ORINS Annual Report, 1956

ORINS Annual Report, 1965

ORINS Annual Report, 1966

From the Beginning

William G. Pollard- ORPL Digital Collections

A Deacon at Oak Ridge | The New Yorker, published Feb. 6, 1954 (Reporter Daniel Lang)

Article “The Coming of Age of Southern Universities in Science” (by William Pollard, 1980)

Dr. William G. Pollard, "Dark Age in the Twentieth Century" (1963- Augsburg University Archives)

Pollard’s sermon about nuclear warfare, published by The Oak Ridger on Friday, July 23, 1982

Article “William G. Pollard: Man of Science, Man of God” (Oak Ridger, Sandra Plant)

Pam Bonee, ORAU communications director